More than 2000 Senegalese and Ivorian fishers who work on board 60 EU distant water fishing vessels went on a strike for 4 days in early June over poor pay and working conditions.

In an unprecedented coordinated action backed by the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF), these crew demanded better salaries, as, according to press reports, some of them are paid “as little as 219$/month”, which is well below the seafarer’s minimum wage (658$) set by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

The tuna vessels on which they work operate under Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreements (SFPAs), which bind EU fleets to ensure environmental and social sustainability of their operations. In SFPAs, operators have an obligation to embark a certain number of fishers from ACP countries, with a priority given to local fishers.

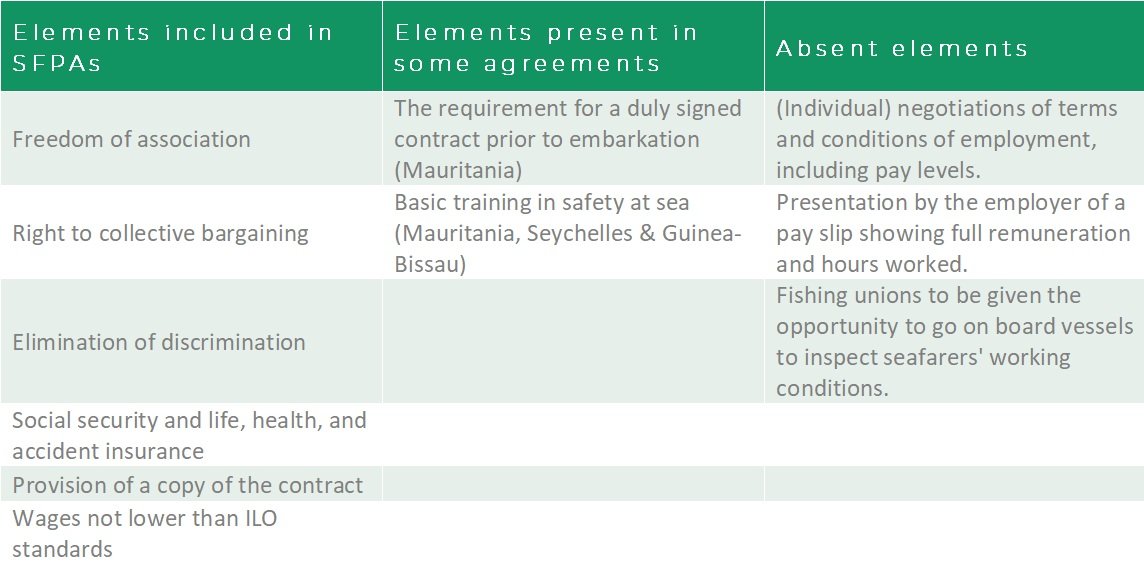

In 2014, European social partners – shipowners and unions – gathered in the Sectoral Social Dialogue Committee in SeaFishing (SSDC-F) agreed on a social clause to be inserted into SFPAs to guarantee decent conditions for non-European fishers. This clause stipulates that the 1998 International Labour Organisation (ILO) Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work and the eight fundamental ILO conventions apply to fishers on board EU vessels. It also covers remuneration levels, negotiation procedures, pay slips and employment conditions for fishers.

A complete social clause – yet not fully implemented

The adoption of the social clause is a positive development, however there are key elements that are missing in the SFPA texts approved after 2014 (see table below), and some that are included on paper, but not implemented.

To improve the working conditions of third countries fishers embarked on EU vessels fishing under SFPAs, the EU Long Distance Advisory Council (LDAC), an advisory body to the Commission regrouping shipowners, unions, and civil society organisations, of which CFFA is a member, published an advice last year on the EU social dimension of Sustainable Fisheries Partnership Agreements (SFPA) between the European Union and third countries.

The advice calls for a “full implementation of the social clause” and for minimum standards for work in fishing under SFPAs. It is issuing recommendations both to the Commission and to shipowners. For example, it reminds fishing vessel owners of the guidelines for vessel owners on decent recruitment of migrant fishers, and recommends the use of model contracts, to “reduce crew vulnerability and contribute to prevent situations such as precarious conditions or labour abuse.”

One of the main issues with the embarkation of non-EU fishers is the fact that EU shipowners hire them through fishing agents. These actors facilitate the operations of industrial fishing in Africa, and in most countries, the services of a local agent are mandatory by law. However, the use of these fishing agents can be a source of corruption and unethical business practices. Several fishers’ representatives have highlighted irregularities in the contracts signed between the fisher and the agent, and the opacity in the setting and payment of wages. They often do not receive a copy of the contract before embarkation and there are many cases of no registration or fictitious registration with social security funds. Shipowners have the tendency to simply blame the fishing agent for not fulfilling their obligations, yet, the LDAC noted that it is clearly the responsibility of the shipowner to “ensure fisher’s work agreements are respected.”

The advice also asks that the European Commission improves regulations “on the role and accountability of crewing agents.” In its response to the LDAC, the Commission remains silent on this recommendation. It only argues that they while they “encourage vessel owners and crewing agents” to be transparent and accountable, such as regarding the entitlement for fishers of receiving a detailed payslip and signing a receipt for the salary, they “cannot interfere in a private legal relationship, taking place outside of its jurisdiction.” This response falls short of the mark, in as much as the European Commission has the responsibility to ensure that the SFPAs, including its social aspects, are well implemented.

Another aspect that comes into play is the lack of training of fishers. In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, according to local sources, no qualified crew has embarked on EU tuna vessels since 2007. This has an impact on wages as well, as the salaries for simple deckhand fishers are lower. It also happens, that even if some fishers are qualified, they are not necessarily embarked. Fishing agents often recruit the crew, which presents “concerns of kickbacks, or giving jobs as favours to people,” with some fishers reporting up to 1000€ must be disbursed to be guaranteed a job on an EU vessel.

On training, the LDAC notes the challenges for EU fleets to take onboard properly trained fishers and states “since the Union negotiates [..] SFPAs […], it is the Union’s responsibility to ensure that local fishers […] comply with the training and certification requirements of the flag States.” The advice also suggests that sectoral support funds are used to train and upskill fishers. As it has been done in other SFPAs, such as Mauritania’s, the EU should make sure that boarding of a seafarer is linked to a training.

A useful ILO convention – yet many parties have not ratified it

In its response to the LDAC advice, the Commission agrees that “enforcement procedures are crucial to ensure proper implementation” of the social clause, and that in the absence of a specific directive, the enforcement procedures are regulated by ILO conventions, but “they remain under the responsibility of Member States.”

On social security, for example, the LDAC denounces that “current SFPAs do not provide that clarity and seem to place the responsibility for social security protection on the fishing vessel owner” and asks that the responsibility is clarified. On this the Commission responded that “each Member State is free to determine the details of its own social security system.”

All these issues are well addressed in the ILO Work in Fishing Convention 188, which seeks to ensure decent working conditions on board fishing vessels and addresses several aspects that were missing from previous instruments, such as repatriation or medical care. This document was adopted in 2007 but still has a very low ratification level, even among EU Member States. So far, only 7, Denmark, Estonia, France, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, and Portugal have ratified it, while in Spain, it will enter into force in February 2024. Furthermore, very few of the African countries which have signed an SFPA with the EU have ratified the Convention, only Morocco and Senegal, and many countries still have no decree of implementation.

The C188 also covers small-scale fisheries, which means that ratifying countries need to develop legislation to promote safe and decent working conditions in small-scale fisheries, despite the relatively informal nature of the sector. The instrument recognizes the shortcomings and lack of infrastructure for artisanal fisheries and provides for a progressive implementation. The African Confederation of Artisanal Fisheries Organisations (CAOPA) has been calling for more African states to ratify the convention and develop the necessary legislation to fully implement it.

The EU should lead by example, also on working conditions

The public is aware of the abhorrent conditions of African fishers working on board Asian-origin vessels reported by several NGOs and media in the last few years. Yet, if the EU wants to be a champion of ocean governance, and make its fishing agreements real partnerships based on social and environmental sustainability, this should be reflected in the way EU vessels employ and treat the African fishers.

The EU must be irreproachable. Even though much has been achieved, implementing better the social aspects of SFPAs is an opportunity for the EU to lead the way and ultimately bring other fleets of foreign origin fishing in Africa and other developing countries, to offer decent conditions to the people working on board their vessels.

Banner photo: A worker aboard a trawler, by Selene Magnolia/We Animals Media.

The EU Long Distance Advisory Council (LDAC) and CFFA have published the report of the seminar on European fishing investments in third countries they jointly organized last May in Berlin, in the headquarters of the NGO Bread For the World.