with mamadou aliou diallo

This article was written and illustrated in collaboration with Aliou Diallo, reporter and communications officer for the African Confederation of Professional Organizations of Artisanal Fisheries (CAOPA).

Along the road between Cotonou and Togo, fishing communities grow vegetables when "the sea doesn't give enough".

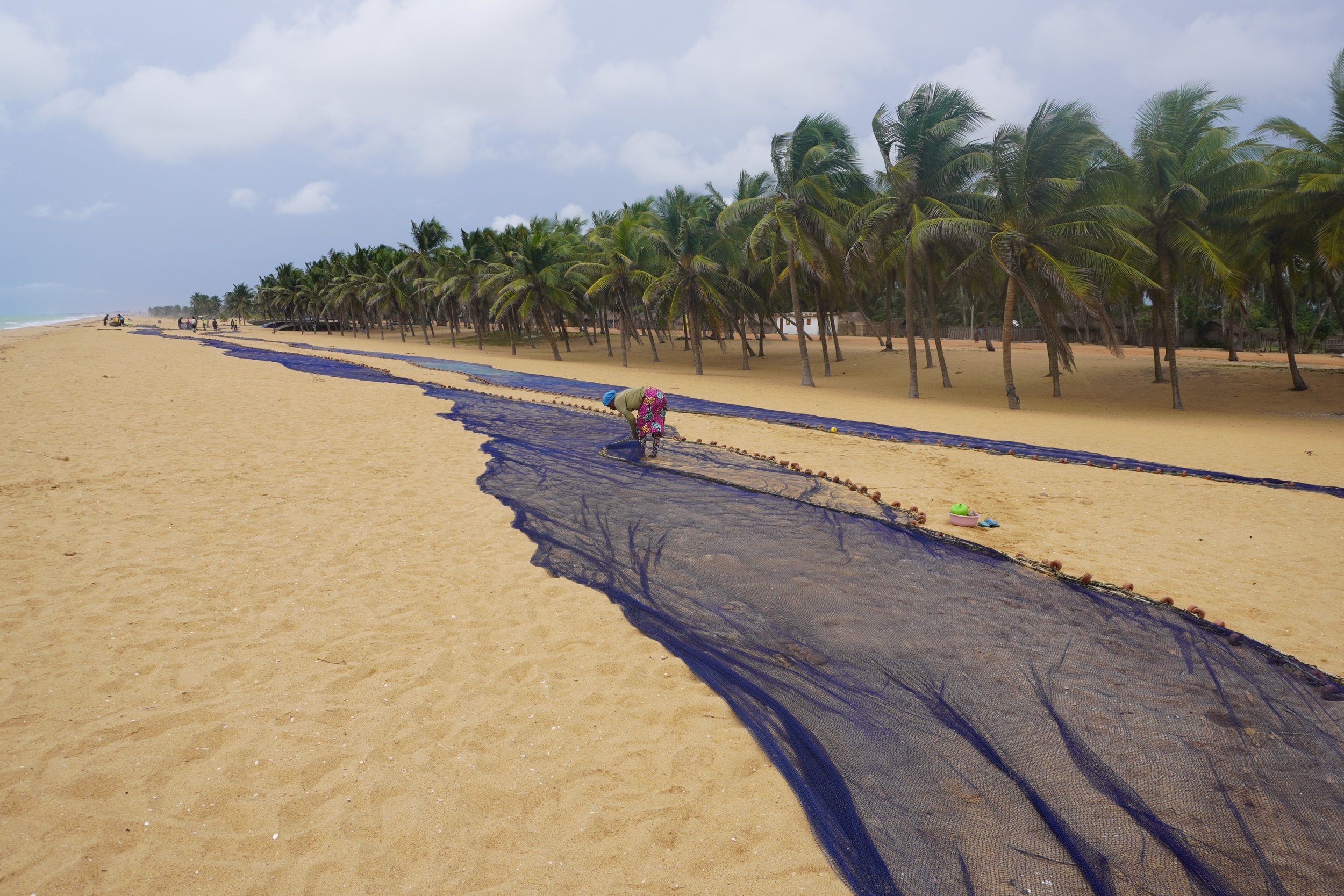

Plot after plot, it is green and fertile. The sandy soil produces onions, carrots, beet, lettuce, and peppers. Occasionally, across the fields, we see two parallel lines of people towing ropes to the shore: they are working with a beach seine, a traditional fishing method practised all year round.

On the border with Togo, in the municipality of Grand-Popo where fishing is the main activity, beach seines can be seen every few kilometres. Early in the morning, the first wing of the net is fastened ashore to a coconut tree or a pole in the ground, then it is set out into the sea by a pirogue, which then returns to the beach to tie the second wing of the net to land, forming a semi-circle. Then the fishers line up and start pulling on each side. This can last for hours, or even a whole day, depending on the ocean current. When the current flows from west to east, the net returns faster to the beach and supposedly catches a lot more fish.

We made a stop in Agoue, one of the 60 villages of the Grand-Popo municipality. Here, the beach is immense, but has only been so for the last few months. Financed by the World Bank, a project of the Dutch company Boskalis has protected and restored over 40 kilometres of beach. The palm trees have just been planted and are too small to cast any shade. We observe a first group of people pulling a rope 200 meters away. The second line is too far. Zéphirin Amedome, a member of the community and owner of two purse seines [Editor’s note: a net encircling fish], sits on a beached pirogue: "All we have to do is wait for them to get closer." Really? They seem a long way off. But the current is from west to east, so it pushes the net and its bag towards us.

A team activity lasting an entire day

Zéphirin was right: twenty minutes later, the fishers pull the rope over the parked pirogue. Under the beating sun, we remain seated on the pirogue while the men and women continue to heave. A young man holds a bell, which he rings constantly and rhythmically, giving a cadence to the collective effort. As time passes, more people join the group, seemingly appearing from nowhere. The beach seine is a community gathering: children, women, fishers, young Nigerian migrants who have come to find their fortune, all trying to get their little piece of the pie.

Zephirin explains that the fishing master, who runs the seine operations and is different from the owner, knows the community very well, and that he will divide the catch once the net has been hauled out of the water and the owner has taken his share. The latter does not arrive until late afternoon when he receives the call that the net is reaching the shore.

We slip away to fetch some water. On the way back, Zéphirin parks the car further west. We settle in the shade of another pirogue and wait for the seine, which has moved another few hundred meters. The two parallel lines are now closer together, and beyond the lines of people pulling, a few women are untangling the part of the net that is already on the sand while somegleaners remove the small fish caught in the mesh along the net.

Meanwhile, some other younger women start to bring back the ropes and the first parts of the net, while the men continue to pull. They roll up the net in their basins, place them on their heads and walk in line to lay the net at the fishing master's feet. Nearby, net menders repair the holes in the net.

When the sea is generous

Several women fishmongers arrive, place their basins on the ground and sit in them. Around them, other women take the opportunity to sell their goods: water sachets or puff puffs [Ed. African beignets, as called in West Africa]. It is as if they had been warned that it would not be long now because, all of a sudden, everything happens very fast. The younger ones start shouting, and the rest of the net is hauled with the bag, loaded to the brim with juveniles of all kinds, a few shrimps and one or two small sole or barracuda.

The bag is untied from the net and the fish are pushed to the bottom of the bag. You can feel the excitement around the bag, yet no one dares touch the catch until the fishing master gives the order. Sometimes people must wait for the owner of the seine, other times the fishing master wants everyone to untangle, clean and stow the net back in the pirogue, so that everything is ready for the next day.

But now it is time for the fishing master to divide up the bounty. The younger women now use their basins to measure the catch and make small piles. There are different sizes of basins: small (10-15 kgs), medium (15-20 kgs) and large (20-25 kgs). Zéphirin explains that "the choice of a basin or another depends on demand and the size of the day's catch". The best catches are kept for the owner of the seine, who appears discreetly and stands aside.

Time for a closed season?

This subsistence fishery is considered unsustainable due to the large number of juvenile catches and the risk of marine mammal bycatch. Zéphirin Amedome, who is also Secretary General of the National Union of Fishers, Sailors, Craftworkers and Assimilated Workers of Benin (UNAPEMAB), points out that it is important for the administration to communicate well on fisheries management measures: "Community awareness is the basis of any good relationship. When there is communication, it brings good dynamics".

Environmental NGOs understand this principle, as they raise awareness about sea turtles among coastal communities. "With a bit of luck, we'll see a turtle", says a member of the local fishing community, but he quickly pulls himself together: "Of course, we hope to find it alive and release it”. Ecoguards often come from fishing communities themselves, so they understand what is at stake. When a turtle is found dead, the ecoguard looks for the cause of death - net marks mean that the turtle has not been killed by the fishers. If that is so, the turtle is then cut up and shared among the community, as turtles are still considered a delicacy throughout the area.

For the first time this year (it is November 2023), several countries in the Gulf of Guinea, in collaboration with FAO, have implemented a closed season for beach seine, although it did not happen simultaneously in all countries. Zéphirin is looking forward to May 2024, when there should be a regional closed season: "If the government, for our future, tells us that we have to do it, it would be salutary, for the well-being of our communities".

Banner photo: Beach seines are community gatherings, where everyone put the shoulder to the wheel, whether they pull, glean, untangle the net, roll it up and put it back in the pirogue. CFFA photo.

Francisco Mari, advocacy officer for global food security, agricultural trade and maritime policy at Bread for the World, reviews the WTO agreement on fisheries subsidies; following its recent entry into force. For this, he points at what till remains unaddressed and the costs and opportunities for developing countries, including the impact on small-scale fisheries.